Photo by Museums Victoria on Unsplash

Author’s Note

When long weekends roll around, I try to take a moment to remember why the holiday exists at all.

Labor Day is one of the few nationally observed holidays in the U.S.—nearly universal in practice, and yet nearly silent in meaning. Most of us inherit it as a pause at summer’s end, not as the marker of protest, sacrifice, and transformation that it once was.

This isn’t a manifesto, and it’s not a lecture. Just a chance to remember what was fought for—and what still slips away when we stop paying attention.

If you have the time, I hope you’ll read.

—Dom

The grills fire up, the flags wave, and for most of America, Labor Day has become little more than the unofficial end of summer. A long weekend, a final day at the lake, a sale at the mall, a pause before the school year grinds into rhythm.

But the holiday was not born from leisure. Like many others, it was born from conflict.

In the late 19th century, when twelve-hour shifts and six-day workweeks were the norm, workers gathered to demand safety, dignity, and the radical idea that a life might mean more than endless toil. They marched through streets where children labored in factories, where men died in mines, where women worked themselves into early graves. And for daring to ask for limits, for rest, for recognition, they were beaten, arrested, and in some cases, killed.

The day was carved out of that struggle. It was meant to remind both worker and owner that labor is not disposable, that progress is built on sweat, sacrifice, and solidarity. Yet over time, that origin has been scrubbed into something polite, almost forgettable. The cookouts remain, and most people get the day off, but the conflict has been erased.

Recommended Listening:

The Origins

Labor Day emerged from one of the most turbulent chapters in American industrial history. The rise of railroads, steel mills, and textile factories created unprecedented wealth for a few, and unbearable conditions for the many who built it.

Wages were meager, hours unrelenting, and safety an afterthought. A single injury could cost a worker his livelihood, with no compensation or protection. Women and children were paid a fraction of men’s wages, yet faced the same deadly machinery. The American dream was held just out of reach for many who sustained the very engines of its rise.

These were not abstract grievances. They were the reality of breadwinners collapsing after sixteen-hour shifts, of children missing fingers from textile looms, of miners never returning home after cave-ins or explosions. The call for change crystallized into a simple but revolutionary demand: an eight-hour workday, with time to rest, to learn, to live. That demand became the rallying cry behind countless strikes and demonstrations.

Strikes swept the country in the 1870s and 1880s, from the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 to the Haymarket affair in Chicago. It was there that the spark truly ignited, when workers rallying for the eight-hour workday were met with bombs and bullets. Dozens died, and hundreds were injured, but the call for justice only grew louder.

In 1894, following the bloody Pullman Strike that shut down rail traffic nationwide and left workers dead at the hands of federal troops, Congress rushed to pass legislation establishing Labor Day as a national holiday. It was, in part, a concession; a symbolic offering to quell unrest. Yet even as it was granted, the choice of September over May 1 (International Workers Day) was deliberate. Unlike the global version of Labor Day (or May Day), celebrated as a show of worker solidarity, America’s version sidestepped its radical roots, reframing it as a patriotic, domesticated holiday.

To understand Labor Day is to remember what it cost; and to ask, quietly and uncomfortably, what parts of that progress we have let slip away.

The Point

Labor Day was never meant as a mere pat on the back, a perfunctory “thanks, workers.” It was a marker of demands wrested from power: the insistence that human beings deserved dignity, safety, and fair wages. The existence of the holiday itself testified that labor could not be ignored or endlessly consumed.

But its official recognition also carried compromise. By creating a government‑sanctioned day, legislators sought to transform a movement rooted in protest into something more orderly and acceptable. The September date was part of that bargain: a way to acknowledge workers without endorsing the more radical, internationalist calls of May Day. In effect, it was a promise—labor would be honored, but within boundaries set by the state.

The point, then, was twofold. For workers, it was a hard‑won acknowledgment that their collective strength had carved out real concessions: shorter hours, safer conditions, and the legitimacy of organizing. For employers and politicians, it was also a tool to contain unrest, to create a ritual that could honor labor without encouraging further disruption. The day signified not only victory, but also containment.

It marked a deeper shift—the recognition that work could be organized, and that through solidarity, power could be shared.

The strikes, boycotts, and marches were not only about hours or pay, but about voice and agency: the right to shape the conditions of one’s own life. That is the point we often forget when we reduce Labor Day to a long weekend: it was born from the radical idea that workers were not simply tools, but people with the collective strength to change the world of work itself.

What Was Avoided

Yet even as the holiday was established, much was deliberately left unsaid. The brutality of early industrial labor—the child workers sent into mills and mines, the twelve-to- sixteen-hour shifts that wrecked bodies, the frequent deaths on the job—was quickly softened in the public telling. The memory of blood spilled in strikes was not meant to linger in a holiday designed for parades and speeches.

Equally avoided was solidarity across borders. By rejecting May Day, the United States sidestepped international worker unity and the explicitly political demands tied to it. Instead, Labor Day was localized, Americanized, and ultimately depoliticized. It offered a ritual of recognition without a lasting reckoning, a holiday that honored labor only so long as it did not threaten the existing order.

And yet, beneath (or perhaps despite) what was avoided, real changes did result. The momentum of the labor movement forced legislation: the Adamson Act of 1916 established the eight-hour workday for railroad workers, setting precedent for wider adoption; child labor laws began to take root in the early 20th century; workplace safety regulations emerged slowly but steadily.

Trade unions grew in strength, becoming powerful vehicles for collective bargaining and political influence. From the American Federation of Labor to the Congress of Industrial Organizations, organized labor gained legitimacy that had once seemed impossible.

These victories were incomplete and often fragile, but they proved that workers, united, could wrest not only holidays but laws, rights, and protections from a system designed to ignore them. Labor Day’s existence may have been a compromise, but the broader movement that gave birth to it reshaped the American workplace in ways that still echo today.

Where We’ve Slipped Backward

Since the 1970s, union membership has steadily declined, leaving fewer workers with the collective bargaining power that once secured their rights. In its place, the rise of gig work and contingent labor has eroded traditional protections, shifting risk from companies to individuals while often disguising instability as flexibility.

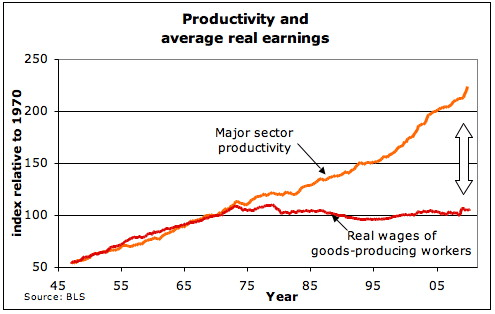

The economic picture tells its own story. Since the mid‑1970s, worker productivity has continued to rise sharply, but real wages for most Americans have remained largely flat, even as efficiency gains have disproportionately favored the top. The result is a growing mismatch between contribution and reward.

At the same time, the cost of labor—from healthcare to housing to education—has outpaced wage growth, placing increasing strain on workers expected to do more with less.

The hiring market has become another source of erosion. Ghost jobs—positions posted without real intent to hire—inflate numbers while wasting applicants’ time, and are only now beginning to face legal scrutiny in some states. Meanwhile, tech and corporate sectors have embraced cycles of overhiring followed by mass layoffs, treating employment as a lever to be pulled for market optics rather than a commitment to human livelihoods.

Return‑to‑office mandates have in many cases been wielded as a blunt tool, not for productivity but as a workaround to avoid official layoffs—forcing attrition by pushing out those who cannot comply. Beneath the rhetoric of culture and collaboration lies a quieter truth: these policies function as cost‑cutting measures, often at the expense of those least able to absorb the blow.

Much of the language once tied to labor struggle has been softened or rebranded. Layoffs, overwork, and denial of basic rights are reframed as issues of “culture fit,” “resourcing,” or “realignment.” But beneath the corporate gloss, they remain what they have always been: fights over dignity, time, and survival.

Another dimension of this regression lies in the broader shift of corporate philosophy. For much of the 20th century, business education emphasized stakeholder responsibility: companies were expected to balance obligations to employees, customers, and the communities in which they operated. But beginning in the 1970s, Milton Friedman’s doctrine of shareholder primacy took hold, recasting corporations as entities with a single overriding duty—to maximize returns for investors.

The costs to workers, neighborhoods, and long‑term stability were downplayed or dismissed. This shift hollowed out the sense of mutual obligation that once tied labor and capital together, replacing it with a calculus that treats jobs, communities, and even entire regions as expendable so long as quarterly profits remain intact.

The neglect of stakeholders beyond shareholders has left scars: shuttered towns after plant closures, underfunded public services once supported by local industry, and a workforce increasingly viewed as a variable cost rather than a vital partner. It is here, in the gap between what was promised and what was abandoned, that the erosion of Labor Day’s meaning becomes most visible.

Conclusion

Labor Day is not just a date on the calendar or a convenient long weekend. It is the inheritance of struggle, sacrifice, and vision—your parents, grandparents, and communities once fought to carve out a better world for workers, neighborhoods, and even companies themselves. What we now treat as normal was once radical, and it came at a cost measured in lives and livelihoods.

But the story does not end with memory. It calls us to shared responsibility. The protections that exist today were not won for one generation alone, but entrusted to the next with the expectation that they would be preserved and strengthened. Employers, employees, policymakers, and communities each hold a part of that responsibility: to ensure that fairness is not an afterthought, that dignity is not negotiable, and that prosperity cannot be sustained when it relies on models that treat people as disposable.

So as the grills fire up and the flags wave, pause for more than celebration.

Stop, reflect, and remember why we have the holiday at all. It is not simply about a day off; it is about the dignity of work, the safety of families, and the recognition that progress requires vigilance and stewardship.

To honor Labor Day is to ensure it does not fade into forgetfulness, but remains a reminder of what was won… and what can still be lost if we fail to carry that responsibility forward together.

Leave a comment