Author’s Note

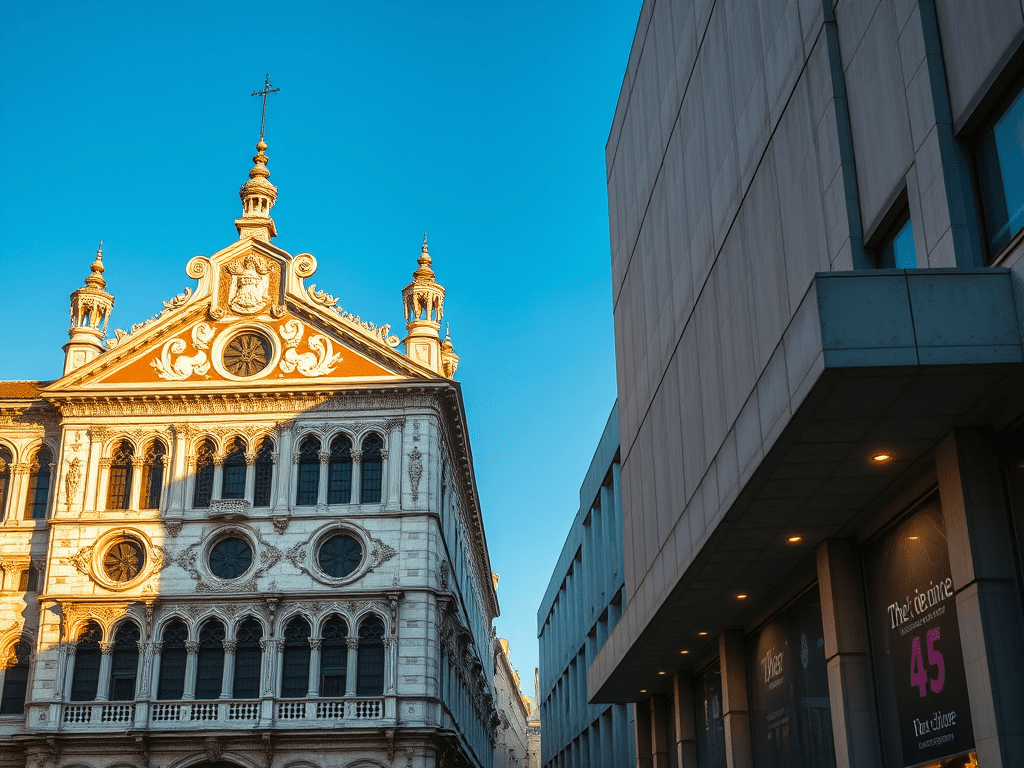

Open a wallpaper gallery and Venice greets you in improbable pastels, each façade pocked by salt, each balcony crooked under centuries of hanging laundry. We intuit the labor and love embedded in every imperfection; beauty is the residue of care over time.

Then the plane lands at O’Hare, and the taxi slouches through an exurban trench of parking lots and efflorescent fast-food. Suddenly the horizon is a ledger: tilt-wall warehouses, chain signage, glass that reveals nothing but fluorescent voids. I spent a week tracing Bernini’s curves; now the only curvilinear element in sight is the freeway cloverleaf.

Urbanist Jane Jacobs warned that “designing a dream city is easy; rebuilding a living one takes imagination.” Our problem is not that we lack imagination; it is that we outsource it to Excel.

This post, the next in the Tools series, anatomizes the architecture of austerity—not only what it looks like, but what it teaches us about who is welcome, how long they may stay, and what it means to belong.

~Dom

The Illusion of Minimalism

True minimalism is a dialogue between presence and absence. A Kahn corridor can feel monastic yet lavish because the stone absorbs noon light like velvet; a Barragán wall reads as a single brush-stroke of color so saturated it seems to hum. Nothing is cheap about such restraint; it is sculpture on the scale of habitation.

The value-engineered “minimalism” of many American developments, by contrast, is subtraction without thought. A contractor erases every line item that is not mission-critical to occupancy permits: no cornice, no depth at the window reveal, no material that might weather into character instead of peeling into neglect. Plastic clapboard mimes wood from the distance of a zoning map; hollow-core doors thud like a reprimand each time they close. When the substitution cycle is complete the project team pronounces the building contemporary—as if contemporaneity were a style instead of a timestamp.

Architectural theorist Nikos Salingaros once observed that the modern box treats occupants as “biological residue left over after the HVAC is sized.” The joke lands because it feels true: the building is not for the body but for the spreadsheet that justified it. We sense, even before we name it, the difference between disciplined elegance and institutional neglect.

Recommended Listening:

Hostile Architecture: Shapes of Exclusion

The sterile city does not merely tolerate drabness; it sharpens it into discipline. A public bench gains three stainless fins, evenly spaced to slice the possibility of horizontal rest into thirds. Window sills grow rows of needles that glint like morning frost. On a Portland light-rail platform, granite blocks are tilted forward by three degrees—imperceptible to the eye, decisive to the tired spine.

The hardware catalog calls these “amenities.” Urban sociologist William H. Whyte’s riposte still stings: “It is difficult to design a space that will not attract people. What is remarkable is how often this has been accomplished.” Every anti-sleep ridge and anti-loiter spike is an architectural sentence that begins, You may pass, but you may not linger. The target is rarely named—the homeless veteran, the under-supervised teenager, the day laborer with nowhere to sit—but the lesson is absorbed by everyone: comfort is conditional; presence must be justified by purchase.

Surveillance & the Panopticon Forecourt

To compensate for its vacancy, the contemporary plaza relies on optics, not experience. The planter walls are low enough to prevent cover; the lighting levels meet security-camera algorithms, not circadian rhythms. You feel watched because you are. During a 1952 address Frank Lloyd Wright condemned the “box” as a “Fascist symbol…anti-individual.” The panoptic square is that symbol unfolded into the urban fabric: the tyranny of uninterrupted sightlines.

Jan Gehl reminds mayors that “first we shape the cities, then they shape us.” A plaza built for visibility teaches citizens to become objects: always on stage, always provisional, never quite at home. Spontaneous music, soapbox speech, lingering eye contact—each feels illicit under the drone of an unseen lens. The city that polices itself architecturally soon needs fewer explicit laws; behavior has already been domesticated by design.

Financial Efficiency as Civic Ethos

Developers arrive at planning hearings armed with three-ring binders of feasibility tables where the words beauty, heritage, and public good never appear—there is no cell for those. The metric that matters is rent per square foot; everything else is exterior finish. Author James Howard Kunstler skewers the mindset: “We have created thousands of places in America that aren’t worth caring about, and when we have enough of them, we’ll have a country that’s not worth defending.”

Efficiency used to mean sparing waste; it now means sparing anything that cannot be monetized in the current fiscal quarter. When vinyl siding fades, it is cheaper to knock the building down than to restore it, because restoration was never contemplated in the spreadsheet’s exit strategy. Lewis Mumford’s quip that “our national flower is the concrete cloverleaf” was a warning; today it feels like botany.

Cultural Erasure by Design

A street is an archive written in brick and stone. Remove the material palimpsest and you redact the memory encoded there: the immigrant mason’s brick bond, the jazz bar that once rattled the windows, the hand-painted sign that pointed to the union hall. Replacement in isolation is not violence; replacement at scale is amnesia.

The cycle is relentless because it is profitable. A CVS leases more reliably than the sandal-maker whose grandfather nailed those window frames; a beige EIFS panel installs faster than hand-troweled stucco. What vanishes is the tale that the city once told about itself. When the facades across five states share the same cladding spec, no passerby can divine whether she is in Nashville or Newark without consulting her phone.

Christopher Alexander’s “single overriding rule,” that each addition must “heal the city,” is treated today as a quaint spiritualism. Yet the cost of ignoring it accumulates interest. We inherit blocks that do not merely fail to delight; they actively degrade the capacity of future builders to weave anything new into their dead grid.

The Commons We Forgot

True public space is an engine of unplanned encounter—ambush guitar duets, impromptu chess, protest that swells by word of mouth. Modern American downtowns rarely tolerate that indeterminacy. Instead we get the privately owned public space, POPS: granite forecourts patrolled by a security firm whose badge is legally private speech. The sign says Welcome; the fine print bans leaflets, sleeping bags, political banners, amplified sound.

Sociologists tracing pedestrian speed have documented a steady acceleration: in Bryant Park the average walker in 1980 ambled at 1.4 m/s; by 2010 the pace had jumped to 1.9 m/s. The sterile plaza is designed for such throughput. It does not want to be a living room; it wants to be a carpeted corridor between point-of-sale and parking meter.

Yet glimmers of resistance persist. In Philadelphia neighbors painted outlaw crosswalks where city engineers dithered; in Tulsa a bar owner dragged thrift-store couches onto an over-paved lot and accidentally launched a weekend bazaar. These incursions feel mischievous precisely because they re-assert the commons we have forgotten to expect.

Tools of Silent Discipline

A city need not post ordinances when its hardware whispers louder. The newcomer learns by osmosis: benches are narrow, so conversations must be brief; awnings are shallow, so rain means retreat indoors; plazas are sun-blasted, so gather only at night, if at all. Even the soundscape conspires—soft jazz piped from lamppost speakers that dull the edge of anger and drown the risk of spontaneous singing.

No act of force is required. The seat whose armrest divides the tired body into non-reclining thirds performs the police work itself. A mother who cannot nurse without shade leaves; a homeless veteran who cannot rest without pain moves on. Discipline has become a background radiation: invisible, constant, reducing the half-life of every unsanctioned human flourish.

Toward an Architecture of Care

The antidote is not nostalgia; medieval grime cannot simply be re-imported. It is the discipline of stewardship. Copenhagen’s harbor baths prove that industrial edge can be re-sewn into civic fabric; Barcelona’s super-blocks show that the curb can be renegotiated in favor of children’s games; New York’s High Line, for all its tourist kitsch, teaches the value encoded in a rusting trestle once slated for demolition.

Care is slow and therefore expensive in the short term, but it amortizes in belonging. A hand-laid brick façade is maintenance-hungry, yet a century later it still holds the interest of the passing child who traces mortar lines with a fingertip. The tilt-wall warehouse is cheaper now and worthless later; the choice is not between frugality and luxury but between transient saving and lasting worth.

The practical program is almost embarrassingly modest: deeper window jambs for shadow play; trees tall enough to outlive the mortgage; benches wide enough for a guitar case beside a stranger. Yet each gesture says, Stay as long as you need; this place expects to love you back.

Conclusion: Reading the Bench Backwards

Every armrest bisecting a bench is a paragraph in a manifesto of exclusion. Every bristling sill is an abstract of which bodies may pause and which must press on. Every barren square hemmed by cameras is a chapter on the economics of suspicion.

Cities draft their constitutions in concrete and steel. When the grammar we build begins every sentence with Move along,we should not be surprised when the citizen finishes it with to somewhere that matters. The most radical civic act is therefore architectural: to carve a niche deep enough for story, to lay a stone stubborn enough to outlast its first use-case, to shape a room where the unknown neighbor feels invited to sit—and maybe to stay until the music starts.

The soul of a city is not a line item. It is the slow, cumulative welcome extended to the stranger who arrives with nothing but faith—faith that the bench, lacking spikes and partitions, was placed there for them.

And the rebellion is simple: to sit. And stay.

Leave a comment