Author’s Note

This essay continues my exploration of humanity’s tools, which began with Children of Hephaestus. That piece explored the external instruments we craft—hammers, networks, algorithms—and the way they amplify our intent, for better or worse.

This one turns inward.

Not all tools are visible. Not all are chosen. Some are inherited. Some are installed by fear, repetition, or survival. Others are written into our neurology, defined by genetics, and honed by eons of evolution—code that helps us tolerate contradiction, excuse harm, and stitch continuity into a self that’s still in flux.

The Dweller on the Threshold is not wielded like a sword—it is inhabited like a shelter. But the shelter is scaffolded with justifications. And over time, it becomes harder to distinguish between protection and prison.

Like all tools, it’s not dangerous because it exists. It’s dangerous because we forget it’s still running.

~Dom

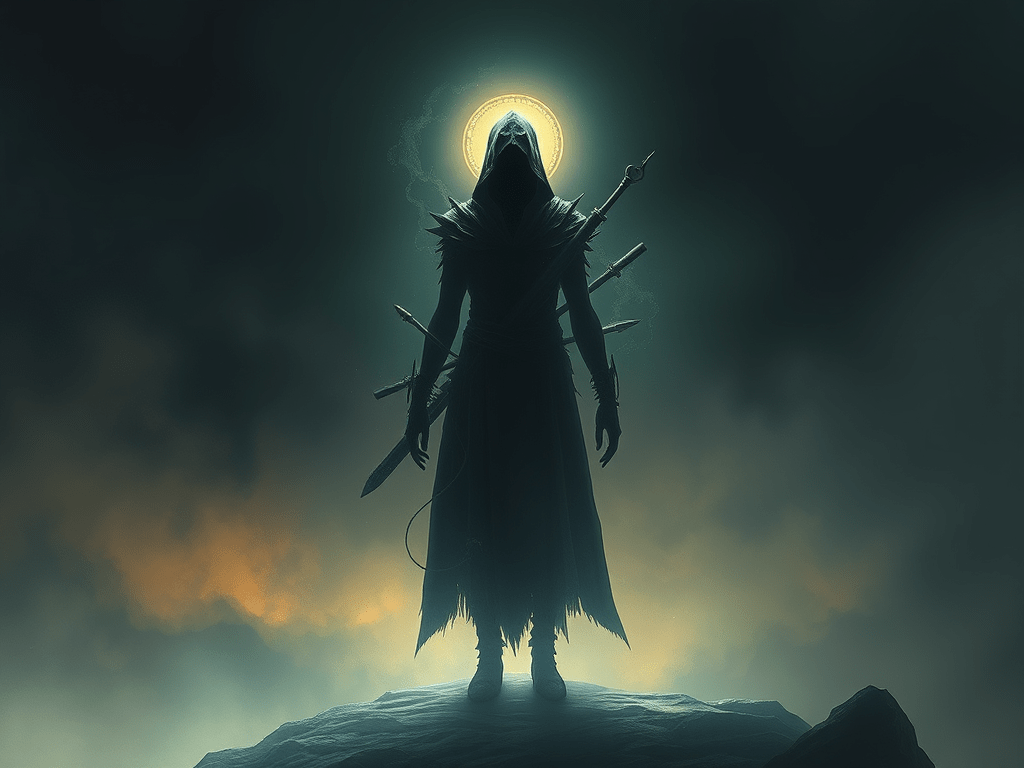

In the shadowed corners of Western mysticism lies a whispered warning: beware the Dweller on the Threshold. The stories agree on only three points. First, the Dweller stands between the seeker and a promised height of knowledge. Second, it never lies—it only remembers. And third, its face is always, unbearably, your own.

Occult handbooks describe the Dweller in the language of initiation trials: a spectral sentinel forged from unresolved debts. Depth psychology nods—this is simply Jung’s Shadow cast onto a mythic screen. Cognitive scientists, less poetic, would track the same dynamic in the anterior cingulate when moral error signals light up. What none of those vocabularies quite capture is the tool‑like precision with which the apparition operates. It is not merely a by‑product of wrongdoing—it is an instrument we build to keep our wrongs in place.

Every rationalized cruelty drives a piton into the cliff face of identity, anchoring the next step in the same hazardous direction. The Dweller is the lattice of those spikes, lashed together with our justifications until the structure feels as immovable as bedrock.

Recommended Listening:

The Tools We Craft · Binding Our Choices

Human history is a chronicle of tool‑making. Spears, ploughs, subpoenas, algorithms—each extends the reach of intent. The Dweller belongs to this lineage, but its jurisdiction is inward. Where a hammer edits wood, the Dweller edits conscience, carving away remorse until a distorted shape feels right.

The dweller has found its place in Psychology; Leon Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance explains the first hammer‑stroke. When actions violate values, the mind may change the action, but altering the value is faster and less painful. The Dweller hands us the smaller bill. Moral disengagement (Albert Bandura) supplies chisels: euphemistic labeling (“collateral damage”), displacement of responsibility (“just following orders”), and dehumanization (“they’re animals”). Confirmation bias tightens every rope, filtering evidence until the scaffold becomes self‑sealing.

The themes it embodies have been explored in Philosophy. Aristotle called the failure to act on better judgment akrasia, but akrasia still aches with regret. The Dweller upgrades the toolset: we do not merely ignore the good—we retrofit the good until it conforms to what has already been done. Søren Kierkegaard would later describe this as despair in defiance: a self that knows it is false yet clings to falsity as identity.

And the evidence of the feedback loop has been observed in Neuroscience. Functional MRI studies show that self‑justification activates reward circuits in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex—the same region that evaluates value. The Dweller, then, is not only metaphor; it has circuitry, metabolism, glucose requirements. Self‑deception literally feeds the brain sugar.

Echoes in the Mirror · The Power of Shared Myths

Why do cultures that never shared a trade route nonetheless share this story? Sociologist Peter Berger calls myths “sacred canopies” stretched over communal life, turning brute fact into moral cosmos. Every society must manage the tension between individual agency and collective cohesion; myths externalize private struggles so they can be debated without naming the guilty.

Anthropologist Mary Douglas noted that communities police moral boundaries as shepherds guard fence lines—by inventing predators outside them. The Dweller personifies inside threats: the rot of hypocrisy, the collapse that begins when citizens stop believing their own virtues. Talking about a shadow‑creature allows the village to condemn betrayal without indicting specific neighbors—until archives, testimonies, or mirror moments force the mask to slip.

Modern media re‑mythologizes the Dweller through prestige dramas and true‑crime podcasts: corrupt cops who still salute the badge, fraud‑heavy CEOs extolling innovation. We binge‑watch because the spectacle externalizes our own flirtations with compromise. The Dweller on screen is safer than the one in the bathroom mirror.

Masks of the Mundane · Tribalism and Indignation

In twenty‑first‑century dress the Dweller swaps robes for hashtags, algorithms, and team colors. Social‑identity theory (Henri Tajfel) explains why: the ego borrows worth from belonging; any data that threatens the group threatens the self. The Dweller therefore reinforces the boundary: They’re lying about us; we’re defending truth.

Indignation is not a flaw of the Dweller—it is its engine. Neuro‑studies show moral outrage lighting up the brain’s reward system more intensely than monetary gain. Each online clash becomes a fresh climbing spike: proof that we are righteous and they malignant. Over time the defensive mask fuses to the face—what Erving Goffman called the “presentation of self” ossifies into a prison. Accountability feels like treason; empathy sounds like enemy propaganda.

The Trap of Sunk‑Cost Morality

Economist Richard Thaler framed sunk‑cost fallacy as throwing good money after bad. Moral psychology reframes it as throwing good character after compromised character. Having sacrificed integrity to preserve comfort, we fear wasting the sacrifice by reversing course.

Here the Dweller exploits loss aversion: the pain of admitting harm already done looms larger than prospective good. Better, it whispers, to double down—vote again for the policy that hurt your neighbor; defend again the lie that safeguarded your status. Each repetition retroactively validates the last, creating what philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah calls an “honor code of refusal”: the collective agreement that surrendering the lie would wound group dignity.

The Widening Gulf · When Return Feels Impossible

Every spike of justification lengthens the vertical drop behind us. Trauma researchers observe the pattern in veterans who justify wartime atrocities to survive acute guilt, then find the revised narrative incompatible with civilian conscience. To reconcile the dissonance, memory edits itself—sometimes literally. MRI scans of moral injury show hippocampal dampening, as if the brain dims the lights where archives are stored.

Sociologically, entire states can enact the same drama. Empires extract wealth, then invent doctrines of destiny to erase the blood‑ledger. The greater the gap between myth and archive, the more aggressively the myth must be enforced—statues, school curricula, “patriotic history” acts. Collective Dwellers demand not only silence but celebration; pageantry is penance deferred.

Philosophical Detours · Freedom, Responsibility, and Bad Faith

Existentialism twists the rope tighter. For Sartre, the terror is that the Dweller cannot be slayed by blaming biology, gods, or algorithms; we remain authors of the script. Bad faith is precisely the decision to pretend otherwise. Heidegger would label the pose Uneigentlichkeit—inauthenticity—in which one flees the call to own Being.

Kant, centuries earlier, issued the most uncompromising verdict: the moral law originates in reason. To violate it knowingly is to instrumentalize others, thus shrinking one’s own dignity. The Dweller in Kantian light is progressive self‑miniaturization: a moral dwarf sculpted from discarded duties.

Nietzsche, often miscast as advocate of amoral power, warned that “he who fights monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster.” Without accountability, will turns inward and rots. The Dweller is rot made conscious.

The Neurobiology of Retreat · Why Shame Hurts‑and‑Heals

Before ascent can resume, the climber must stomach a descent—into shame, remorse, and what Brené Brown calls the “dark swamp of the soul.” It’s not a poetic flourish. Neuroscience confirms the terrain: authentic guilt and shame activate the insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, regions tied directly to physical pain. That’s why accountability doesn’t just feel uncomfortable—it feels like a threat to the body itself. The impulse to retreat, deny, or lash out isn’t weakness—it’s wiring.

But evolution rarely installs a system without purpose.

The very pain that shame evokes becomes a moral GPS—a directional beacon meant to reroute behavior. When felt and faced, rather than numbed or deflected, shame activates pro‑social repair mechanisms: apologies, course correction, restitution, reform. In this way, shame is not inherently destructive. It is the psychic equivalent of a pain response from a wound—if you feel it, there is still living tissue beneath. If you ignore it, infection spreads.

What becomes corrosive is not the shame of your choices itself, but chronic avoidance of it.

In a society, the same dynamic plays out. Collective shame—over injustice, inequality, historical harm—can lead to acknowledgment, reparation, even healing. But when that shame is buried beneath national pride, reframed as persecution, or displaced onto scapegoats, the result is rot. The Dweller metastasizes. The group begins defending not just its past, but the very mechanisms that allowed the harm to occur.

And yet, the path back remains.

The moment shame is accepted—when it is held long enough to feel the ache and not flee from it—neuroimaging shows that compassion, empathy, and moral reasoning begin to re-engage. The prefrontal cortex lights up. The self, no longer shielded by denial, begins to move again. Not comfortably. Not quickly. But forward.

This is the final truth of the Dweller we build:

It will not kill us. But we must let part of ourselves die. You can’t turn back. Not with the wall still in place.

The part that refused to feel.

The part that clung to the mask.

The part that called harm necessary, and made it so you never had to look back.

Only then can the real work begin—not of forgetting the past, but of earning the right to live beyond it.

The Courage of Unbinding

So we arrive at the precipice. Shame tolerance—the ability to endure exposure long enough to repair—is the psychological name for the key. Criminologist John Braithwaite calls its social analogue reintegration: restoring transgressors through acknowledgment and restitution rather than exile. Philosophy still calls it the same old word—responsibility.

To pass the Dweller we must perform tool‑work in reverse: extract the pitons. Each owned wrongdoing loosens the scaffold. The neurobiology of empathy (medial prefrontal, temporoparietal junction) re‑awakens when rationalizations cease. No exorcism is required—only truth, spoken without anesthesia, followed by reparative action.

The Dweller is not an executioner awaiting us at the summit. It is a mirror bolted to the wall halfway up, demanding eye contact before we climb higher. “You built me,” it says. “You may dismantle me.”

That is the final choice: keep climbing a scaffold that demands fresh spikes, fresh targets, fresh indignation—or pause, turn inward, and begin the slow, bruising work of unbinding.

Freedom, in the last analysis, is not a prize at the mountaintop. It is the empty space left when the Dweller’s shadow finally breaks and the climber plants both feet on ground made level by honesty.

“Will you finally see clearly what you’ve become—and still choose differently?”

Leave a comment