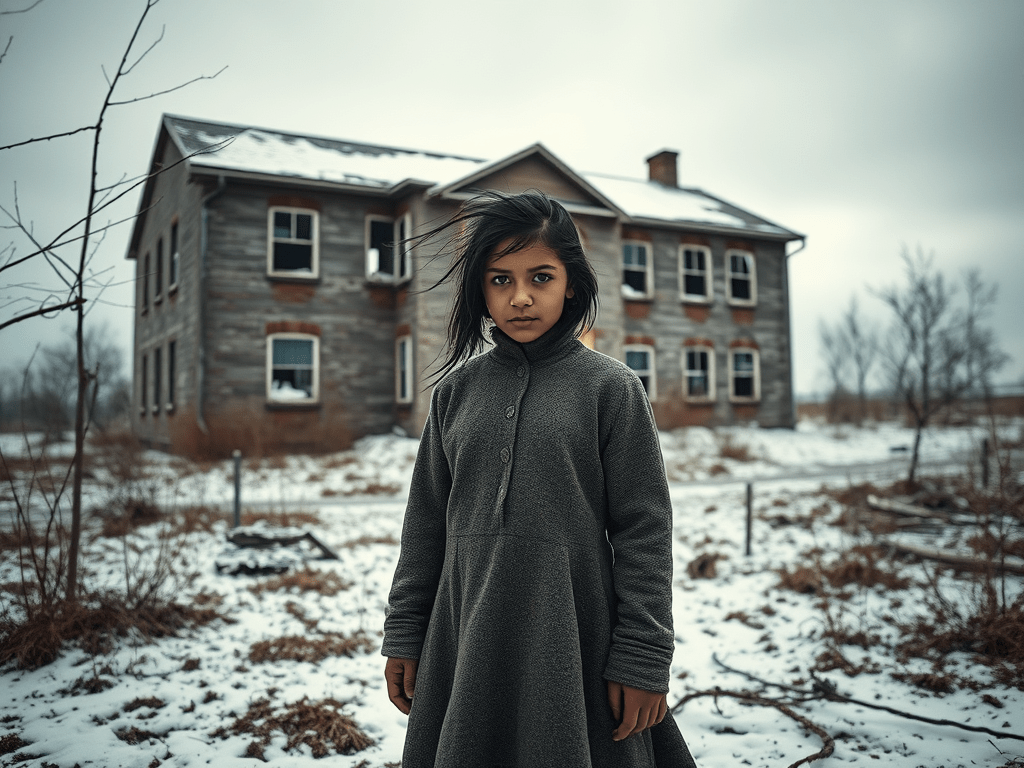

The cold bit through her thin sweater as she walked beyond the sagging gates. Snow crunched underfoot, and the wind whipped across the barren yard. She was only thirteen. Yet her eyes—already too old for her face—scanned the cracked building one last time. Windows like hollow eyes, rusted pipes, a silent chapel bell. Everything about that place screamed neglect.

They told her she could go home.

There was no grand gesture, no triumphant chorus. Just a clipboard, a set of keys, and the nod of an indifferent officer who never bothered to learn her name. He gestured down a path leading to a dirt road. “You’re reformed,” they said. “You know how to behave now.”

Behind her, the building loomed as if it wanted to swallow her whole. Inside, there were still children—dozens of them—who wouldn’t leave today. Some, she suspected, would never leave at all. Their laughter had died long ago, replaced by the hush of dread. She was leaving, but not truly free; the nightmares had latched on, like barbed wire in her heart.

She was Number 47. For years, she’d heard her identity boiled down to two digits. “47, line up.” “47, no talking.” “47, scrub the floor until it shines.” They never said “sorry.” They said, “You should thank us.”

Her hair had been cut jagged, without ceremony. She still felt phantom tugs where her braids once hung. Her sister’s hair was on that same cold floor, braided strands like severed roots. But her sister was gone now—sent to a different ward, or worse. The girl wasn’t entirely sure. She only knew that, at night, some children vanished. They were said to have “run away.” In the dormitories, no one dared speak the truth aloud.

She walked on. She could still taste the soap they forced into her mouth every time she slipped and spoke her own language. The slap of rulers on small hands echoed in her memory. That stench of sour wine and old guilt from the priest who came in the night. No one told her to hold on to her name. It was something she had to remember herself, in quiet defiance.

“They told us to remember our number, instead of calling my name, they’d call my number… Mine was 989.”

— Lydia Ross

There was no parade to mark her departure. There was only the promise, “You can go home.” Yet the cost of that promise clung to her skin like scars. She looked at the road ahead, heart pounding with a single thought: Who will believe what they did to us?

Recommended Listening:

What Stories Tell Us a Villain Is

Popular culture loves its villains big and brazen. They arrive cloaked in black, voices dripping with menace. They grandstand with flamboyant monologues, scheming for ultimate power or revenge. Their eyes might glow red, or their laughter might thunder across the room. It’s a spectacle of evil—thrilling, obvious, and carefully separated from the everyday world.

Fictional villains give us clarity. We know who to root against. We see them twirling mustaches or unleashing diabolical plans. Their motives, no matter how convoluted, still revolve around these overt hallmarks: greed, jealousy, hunger for control. Even so-called “complex” villains tend to follow a pattern that sets them apart from “ordinary” people. They broadcast their darkness with costumes, scars, or menacing theme music.

We crave that clarity. We want to believe that evil is an outsider—something we can spot from a mile away, something that arrives with a snarl and a menacing grin, something we can defeat with a single, decisive act. Like flipping off a switch, good triumphs and evil collapses. The end. Credits roll.

This is the evil we want to see in our bedtime stories: a malevolent force that has no place in polite society, no seat in our churches, schools, or government offices. It exists solely in the realm of nightmares and cinematic showdowns, where it’s always someone else’s problem. We finish the story satisfied, secure in the knowledge that we ourselves could never harbor such darkness.

What Evil Actually Looks Like

But real evil does not wave a banner. It sits at a desk, signs documents with official stamps, and recites prayers in a soft, measured voice. It can wear polished shoes, adjust a neatly pressed collar, and greet you with a serene smile. It officiates ceremonies, organizes charitable drives, and makes “responsible” decisions that, piece by piece, grind vulnerable people into dust.

History brims with examples of such methodical horror. Across continents and centuries, atrocities have been justified by official seals and moral mandates:

- The Spanish Inquisition: Pious officials in robes meticulously recorded each interrogation, torture, and execution, claiming they were saving souls. They wore crosses, not capes.

- The Third Reich (Nazi Germany): Evil arrived in crisp uniforms and typed directives. Bureaucrats filed paperwork that sealed the fates of millions. They believed—or pretended—that they were defending the Fatherland.

- Japanese Experiments in WWII: Under the guise of medical research and national pride, human lives were treated as disposable. Quietly, in hidden facilities, atrocities were committed while official seals guaranteed funding and secrecy.

- The Native American Genocide and the Trail of Tears: Signed treaties broken, forced marches mandated, entire tribes displaced or annihilated—all through government orders that spoke of “progress” and “expansion.”

- Indian Residential Schools: Evil arrived bearing titles like “priest,” “nun,” “teacher,” backed by government budgets, church mandates, and a society complicit in the lie that “civilizing” Indigenous children required stripping them of their language, culture, and identity.

The priests who prowled the corridors at night believed—or at least claimed—that they were “saving souls.” They oversaw brutal punishments for the smallest infractions and silenced any opposition with moral or legal authority. Every ledger was balanced, every form neatly filed, ensuring the machinery of destruction kept turning.

Real evil is not always loud or outrageous. It is often quiet, patient, and entrenched in systems designed to crush those deemed “lesser.” Numbers replaced names. Children stood in line, segregated by labels that stripped them of personhood. And in that dehumanization lay the seed of atrocity.

The Quiet Truth About Evil

Real evil often calls itself good. It prides itself on virtue, discipline, loyalty. It tells you it’s there for your benefit—“We’re doing this to protect you,” “We’re saving your soul,” “We’re defending civilization.” A bishop might sign off on torture “for the faith.” A commanding officer might load trains bound for death camps “for the homeland.” A government official might rationalize forced relocation “for expansion and unity.”

“The bureaucrats were accountable to their political masters, not accountable to the people whom they were overseeing. And putting it as bluntly as possible, no government ever won votes by spending money on Indians.”

— Charlie Angus, Children of the Broken Treaty: Canada’s Lost Promise and One Girl’s Dream

Society, meanwhile, tells us to fear the stranger—the masked intruder or the unknown assailant lurking in alleyways. Yet statistics show that your abuser, rapist, or murderer is far more likely to be someone you know, often in a position of respect or authority. The smiling neighbor, the trusted coach, the beloved pastor who would never raise suspicion. Evil finds the easiest footholds where trust is guaranteed, and scrutiny is discouraged.

It preys on the young, the marginalized, the powerless. In the hush of midnight corridors, it enacts unspeakable acts on children who can’t run away. When a child wets the bed because nightmares crowd her sleep, the staff hand her a brush and a bucket of lye, telling her she has sinned. She must scrub until her hands bleed. And so it continues, feeding off silence and overshadowing dissent.

Cruelty does not always appear as a singular, horrific event. Often, it’s the slow, methodical theft of identity. You’re told to speak only English, to pray in a language you do not understand. You watch as bits of your culture are labeled “heathen” or “primitive.” Eventually, you don’t just lose your language; you lose yourself.

Ask survivors of these schools—or of any institution built on forced assimilation—and they won’t describe monstrous figures with glinting, sharp teeth. They’ll describe nuns who insisted on prayer before administering beatings, priests who smelled of stale wine, officials who typed up reports about “progress.” They were ordinary men and women, going about their duties in the name of God or country. That is the horror of it.

Why We Prefer the Fiction

In stories, evil is defeated by a bold hero or a magical artifact. In real life, confronting evil demands uncomfortable introspection. If evil can hide behind polite smiles and government seals, how do we know we’re not enabling it? If it can wear a nun’s habit or stand at a pulpit, how do we ensure our trust isn’t misplaced?

“I was just a little girl. I thought I had done something wrong. But it was them. It was always them.”

— Unnamed survivor

That’s precisely why we cling to the theatrical villain in popular culture. It spares us the guilt of complicity. We can watch a dark lord enslave a kingdom and cheer as the protagonist slays him. We leave the theater feeling righteous, certain we’d never follow such a tyrant in real life. Because real evil, we tell ourselves, would be so obvious.

But real evil is rarely obvious. It excels at blending in, adopting the language of virtue—charity, patriotism, loyalty, duty—to mask unspeakable deeds. It thrives where people prefer not to ask questions or assume “the experts” know best. Entire generations were taught that removing Indigenous children from their families was an act of compassion. Similarly, entire populations throughout history were convinced that mass violence or forced assimilation was necessary. The public, eager to believe in a moral narrative, often looked away from the scars accumulating behind closed doors.

It’s easier to watch a fictional villain cackle than to read testimony from survivors of the Holocaust, or Unit 731, or the Inquisition. It’s easier to discuss evil in hypothetical terms than to reckon with real atrocities endorsed by institutions we trusted. By distancing ourselves from these truths, we create fertile ground for them to happen again.

A Haunting Reminder, and a Call to Action

She steps onto the dirt road, newly “reformed,” a child told she can return to a home that may no longer feel like home. Her language is shaky on her tongue; her sister’s fate is uncertain. The bruise of memory throbs with each step. That building behind her still holds children who wear numbers instead of names. She was never just a number, but she’ll never forget the years in a place where that’s all she was.

The real villains in her story do not vanish into swirling capes. They remain in the worn chairs of that institution, marking attendance, signing forms, punishing any sign of resistance. And across the world, from the aftermath of the Crusades to the echoes of the Third Reich, from the forced marches of the Trail of Tears to the hidden wards of wartime experiments, new bureaucracies and justifications keep old cruelties alive.

If we want to break this cycle, we need more than a single hero brandishing a sword. We need recognition that evil can flourish under the guise of duty or morality. We need the moral courage to question systems that demand silence and obedience, especially when vulnerable populations—children, minorities, the disenfranchised—are at risk.

Real villainy isn’t always a dramatic showdown; sometimes it’s the slow erosion of human dignity by a thousand small cuts. And real heroism isn’t about slaying a mythical beast; it’s about shining a light into those everyday shadows where small acts of cruelty hide. It’s about refusing to let the status quo stand when it devours innocence.

Look around: what do we shrug off because it’s easier than confronting it? Which institutions do we revere without question? Whose stories do we dismiss because they clash with our comfortable narratives? Evil persists when we turn away, labeling it a relic of history or an anomaly in a faraway land.

But it never really leaves. It adapts. It finds new forms, new justifications, new victims. And it will remain until we learn to see through its disguises—to recognize it even when it wears a kindly face or a holy vestment.

Justice begins with recognition. The child who leaves the residential school behind carries the echoes of those who never left. If we refuse to hear those echoes, if we continue to label these stories as “isolated incidents,” we allow evil to root itself in fresh soil.

“We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

– Elie Wiesel

And still, so many believed it was done in kindness.

Her sister’s fate remains unspoken, like so many others who vanished into silence, but they told her she could go home. She’s just a child, stepping back into a world that might never understand the horrors she’s seen. But if we listen—truly listen—to her story and to others like it, we can name the evil and begin the hard work of uprooting it. That’s the only way the next child doesn’t become “48,” “49,” or “50.”

So ask yourself: if evil rarely looks like the villains we see on TV, how can we spot it in real life? What will you do to ensure another child’s braids aren’t left on a cold linoleum floor — another life, another language, another lineage not lost? Because evil doesn’t need to roar. It only needs silence.

Don’t look away. Listen. Learn. Act. And remember that behind every number was once a name—and behind every name, a life that deserved better than our silence.

Leave a comment