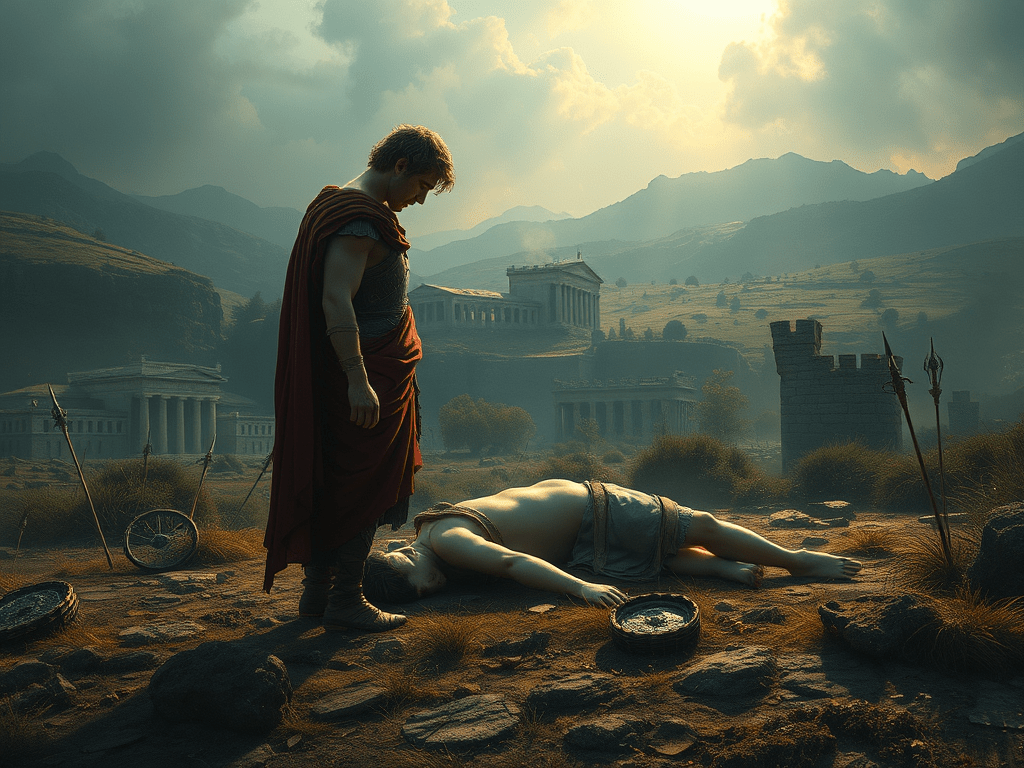

The battlefield was silent but for the wind. Achilles stood over the body of Patroclus, his closest companion, his dearest friend. The price of war had always been clear to him—glory in exchange for life—but until now, he had not felt the true cost. The rage in his chest burned as bright as any funeral pyre, but beneath it, a hollow stretched wide, deeper than the wounds of any spear. Patroclus had donned his armor, fought in his name, and now lay dead for it. What, truly, had been sacrificed? Was it only the life of a friend, or was it something within Achilles himself, something irretrievable?

From mythic tragedies of ancient Greece to the real-life reckonings of revolutionaries, leaders, and lovers, humanity has long embraced the idea that the self must sometimes be cast aside for a greater cause. Parents relinquish their dreams to give their children a better future. Warriors surrender their lives to defend their nations. Reformers burn on the pyres of their ideals. Yet in each sacrifice, something more than the immediately obvious is lost; the very soul of the one sacrificing is altered in ways rarely discussed.

What remains when the triumphant or tragic moment of sacrifice has passed? This question resonates across cultures and centuries. Does the knight who lays down his sword after many battles find peace or a hollow emptiness where purpose used to dwell? Does the lover who forsakes personal happiness for duty discover fulfillment or regret? As we will see, sacrifice has many faces, and the void left behind can be both a haunting absence and a space for transformation.

The Many Faces of Sacrifice

Sacrifice is woven into human culture, morality, and philosophy, yet the definitions vary. Is it a voluntary act of surrendering something precious, or can it also be compelled by duty, circumstance, or even guilt? In countless religious and societal frameworks, sacrifice has been elevated to a noble virtue, one that transcends individual desires for the sake of a higher good.

Religious and Cultural Perspectives

In Christianity, the crucifixion of Jesus is upheld as the ultimate sacrifice—suffering offered to redeem humanity. Hindu traditions, as portrayed in the Mahabharata, frame sacrifice less as loss and more as duty; Arjuna must overcome personal attachments to uphold a cosmic order. Norse mythology presents a direct, visceral example of the price of insight when Odin surrenders his eye to gain wisdom. Across these mythologies and faiths, the core themes remain the same: giving up something dearly valued to serve a cause larger than oneself.

Outside sacred contexts, soldiers throughout history have marched to battlefields with the understanding that their lives may be forfeit for the safety of their people. Parents often sacrifice personal aspirations to secure better opportunities for their children. Even mundane scenarios—like choosing a stable career over a passion project or distancing oneself from loved ones to protect them—can carry the imprint of sacrifice. In each instance, a piece of personal identity is set aside, leaving behind a void that may or may not be filled.

The Glorification—and Its Costs

Society tends to glorify sacrifice. From childhood, we are taught that those who give everything are heroes, that selflessness is the peak of moral virtue. Religious texts, fairy tales, and historical narratives all extol martyrs, saints, and heroes who exemplify noble self-denial. But this cultural reverence can sometimes obscure deeper questions: is every sacrifice inherently good? If an act of self-giving leads to personal destruction—or robs the world of a person’s unique gifts—does it still qualify as virtuous?

In some cases, sacrifice can undermine wisdom. A parent who exhausts every resource might harm their child in the long run by losing physical or emotional stability. Leaders who sacrifice personal integrity for the sake of appearing benevolent can pave the way for greater harm. This tension calls into question the assumption that sacrifice always serves the greater good.

Boundaries of Self-Care and Honesty

When self-care is ignored, sacrifice risks descending into burnout, resentment, or even self-annihilation. Caregivers, for instance, may neglect their own well-being so completely that they become unable to provide meaningful support in the end. Furthermore, sacrificing one’s truth—suppressing desires, ambitions, or individuality—under external pressure can wear down the authenticity that gives life its richness.

As the line between valor and self-destruction blurs, we are left to wonder: how much of ourselves can we give before losing who we are? This question leads us beyond cultural ideals and into the realm of philosophical reflection, where thinkers have long grappled with the paradoxes of sacrifice.

Philosophical Perspectives

Classical Foundations

The tension between individual autonomy and communal welfare has been at the heart of philosophical inquiries into sacrifice since ancient times. For Plato, the well-being of the polis could outweigh the individual’s desires. Yet Plato also championed the cultivation of personal virtue and wisdom, suggesting that the ideal society required balanced, enlightened citizens. Aristotle refined this further with his concept of the “golden mean,” where sacrifice is virtuous only if it stays within a balanced framework—neither self-indulgent nor recklessly self-denying. In other words, giving up everything for the common good is not automatically moral if it destroys one’s ability to function or to practice other virtues.

Kantian Duty and Nietzschean Rebellion

Centuries later, Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative, positing that moral actions are those we can universally will for all beings. This often implies sacrifice—doing one’s duty even when it conflicts with personal gain. Yet Kant also held that each person has inherent worth; to degrade oneself or others in the process of sacrifice violates the very principle of human dignity.

In stark contrast, Friedrich Nietzsche railed against what he saw as a “slave morality”—a cultural ethos that glorifies self-denial at the expense of personal greatness. For Nietzsche, truly noble acts must spring from a place of power and self-affirmation. Sacrifices made out of guilt or compulsion, rather than genuine choice, suppress individuality and weaken society.

Existentialist Questions

Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus further complicated the conversation, arguing that if life has no inherent meaning beyond what we create, then sacrifice must be evaluated on intensely personal grounds. For Sartre, sacrificing yourself for external validation or out of “bad faith” (self-deception) is inauthentic. Camus, who examined the absurdity of existence, posed an unspoken challenge: does sacrifice genuinely give life meaning, or does it merely mask the inherent meaninglessness we refuse to accept?

The mosaic of perspectives—classical, Kantian, Nietzschean, existential—reveals the complexity underpinning the act of sacrifice. Viewed as heroic from one angle, it can appear tragic, even oppressive, from another.

The Psychological Aftermath

Beyond the ethical debates, the aftermath of sacrifice can leave deep psychological imprints on those who give themselves over to a cause. Soldiers often return from war with survivor’s guilt, haunted by what and whom they have lost. Parents who channel every ounce of energy into a child’s future may find themselves directionless once that child leaves home. Activists who devote their lives to social change can grow disillusioned when progress is slow or the movement evolves without them.

A key concept here is “identity foreclosure,” where a person’s sense of self becomes so bound up in a single role or mission that, once that role ends or transforms, they are left adrift. The hollow feeling Achilles experiences—a chasm in his chest—can manifest as depression, resentment, or profound confusion about one’s purpose in life.

The Hollow That Remains: Wound or Space?

This hollow can be a permanent scar, a lingering ache that never fully heals. Alternatively, it can become a space of possibility. Some who sacrifice deeply undergo a kind of metamorphosis—emerging not as diminished versions of themselves, but transformed, with new insights and strengths. However, this transformation requires recognizing and tending to the void rather than ignoring it.

Left unacknowledged, the emptiness can metastasize into cynicism or despair. If someone believes their sacrifice was exploited or underappreciated, bitterness may take root. By contrast, if they approach the hollow with compassion—both for themselves and for the reasons they gave so much—they may find renewed purpose, empathy, or clarity about what truly matters.

A historical anecdote underscores this duality: Simone Weil, the French philosopher and activist, sacrificed her physical well-being to experience the hardships of factory workers. Some see her as a paragon of empathetic sacrifice; others believe her extreme self-denial led to her early death, squandering a brilliant mind. Whether Weil’s story is heroic or tragic depends on how we interpret that hollow space left behind in the wake of her sacrifices.

The Echo of Sacrifice

In the silence after victory and the hush following tragedy, sacrifice reverberates like an unspoken echo. From Achilles’ anguished vigil over Patroclus to the countless tales of parents, revolutionaries, and dreamers, we witness a delicate interplay between giving and losing. The hollow left behind can be a source of relentless sorrow or fertile ground for something new to take root.

Society lauds sacrifice for its moral valor and collective benefit, yet the personal toll can be devastating. Philosophers, from Plato to Nietzsche and Kant to Camus, have wrestled with these moral complexities. Is sacrifice the highest virtue, a necessary evil, or perhaps both? The answer may depend on context, intent, and outcome—on whether the act fosters genuine growth or devours what is most vital within us.

At its pinnacle, sacrifice showcases the human capacity for empathy, courage, and devotion, embodying a willingness to stand for something beyond oneself. But it can also entrap, turning into a prison of imposed duty and self-neglect. Ultimately, sacrifice’s true value lies not just in the act but in the awareness that follows. If we recognize the psychological and spiritual void it can create, we stand a better chance of filling it with compassion, new perspectives, and authenticity.

Is the hollow, then, a wound or a space? Perhaps it is both: a scar marking irreparable loss and a clearing where understanding, empathy, and purpose can be born. In that duality lies the enduring power—and danger—of sacrifice, illuminating why it continues to captivate our moral imagination. The echo of sacrifice lingers in that fragile place between what is given up and what might still be found.

Leave a comment